Contents

- Introduction

- Limits of human knowledge

- Nicholas of Cusa and Immanuel Kant

- Learned Ignorance

- Goethe

- Polarity

- Intensificaton (Steigerung)

- Aurobindo

- Purusha – Prakriti

- Steiner

- Michaelic Yoga

- Concentration and Meditation

- Philosophy

- Purification

Introduction

I want to draw together some threads from Rudolf Steiner, Sri Aurobindo, Goethe and Nicholas of Cusa. These threads seem significant and consequently I feel compelled to set finger to keyboard to clarify an idea that connects the above four people in a meaningful way to the notion of spiritual growth and the transcending of materialism. In abstract it could be described as an example of cosmic Hegelian dialectic searching for a sublimation of the opposites of spirit and matter. It also affords an interesting perspective on the theodicy problem, the problem of finding meaning in the existence of evil, a question that many more people are asking themselves today with renewed fervour.

Limits of human knowledge

Over the past month or so I have been imbibing the spiritual atmosphere of Europe in the 14th and 15th Century. Those familiar with the “human number 666” mysteries will understand the connection between that period and our current period. In the English speaking world two noteworthy titles are The Cloud of Unknowing by Anonymous and The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas á Kempis. The other key ingredient was chapter 4 of Steiner’s Truth and Science, A Prelude to The Philosophy of Freedom, GA 04. More specifically when we are led to understand the consequences of Kant denying the possibility of “intellektuelle Anschauung” (intellectual seeing) for human beings.

Concepts and ideas alone are given us in a form that could be called intellectual seeing. Kant and the later philosophers who follow in his steps, completely deny this ability to man, because it is said that all thinking refers only to objects and does not itself produce anything. In intellectual seeing the content must be contained within the thought-form itself.

GA 4

This seemingly innocuous statement is profound in the context of epistemology, but in order to understand it, it helps to trace it back to its roots, namely to Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464)

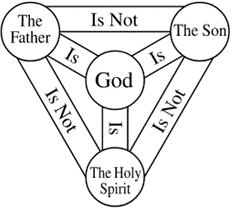

Nicholas of Cusa develops the central concept of learned ignorance. Steiner had many interesting observations on the importance of this idea and goes into some detail in GA 7, Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age (RSArchive). In De Docta Ignorancia (1440) we are introduced to the idea of the limits of reason. I have also dealt with this topic from another perspective in another article on Steiner and Aurobindo called Destiny of the Individual and Ethical Individualism. The notion of learned ignorance was not a new idea as it was also discussed by the early church fathers and important thinkers like Scotus Erigena and Pseudo Dionysius. Essentially learned ignorance refers to the inherent incompleteness of human knowledge and the assertion that God, as an infinite and transcendent reality, cannot be fully grasped by human intellect. In the context of this essay God means knowledge of the spiritual worlds, the hierarchies all the way up to the Godhead. We can also insert here that Steiner might change this slightly to ‘cannot be fully grasped by the intellectual soul or mental representation’. Aurobindo in his language might say ‘cannot be fully grasped by Mind’ at the same time reserving this possibility for the Supermind. Nicholas of Cusa also leaves this opportunity open by asserting that both reason and supra-rational understanding are required to know the spiritual worlds. Here is a selection of some notable thinkers who have also tapped into this, at first seemingly, abstract notion since Nicholas of Cusa. The concepts of negative theology or apophatic theology are also intimately related to Cusa’s concept.

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582), Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), John of the Cross (1542–1591), Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), Paul Tillich (1886–1965), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), Edith Stein (1891–1942), Thomas Merton (1915–1968), Jean-Luc Marion (1946-), Richard Kearney (1954-).

Predating Cusa we also have an interesting list of mystics who challenge the notion of the unknowability of the spiritual worlds.

Laozi (c. 6th century BCE), Rabia of Basra (c. 717–801), Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 5th–6th century), Beatrice of Nazareth (c. 1200–c. 1268), Mechthild of Magdeburg (c. 1210–c. 1282), Jacopone da Todi (c. 1230–1306), Ibn Arabi (1165–1240), Johannes Tauler (c. 1300–1361), Henry Suso (1295–1366), Marguerite Porete (c. 1250–1310), , Jan van Ruusbroec (1293–1381), Angela of Foligno (1248–1309), Meister Eckhart (c. 1260–1328), Julian of Norwich (1342–1416),

Nicholas of Cusa and Immanuel Kant

Let us now try to understand what learned ignorance has to do with intellectual seeing. This concept appears with Cusa in the form intuitus intellectualis. By this he meant that there is a higher form of perception or insight that transcends ordinary intellectual processes and allows for a more direct apprehension of reality, particularly in matters of spiritual and metaphysical nature. The term “intuitus” conveys the idea of a kind of intuitive vision or contemplative gaze, whilst “intellectualis” indicates that this form of seeing is related to the intellect, but it goes beyond the limitations of discursive reasoning. This too is significant in the context of Steiner and Aurobindo, because they also make clear that the spiritual worlds are knowable to human beings, but, as with Nicholas of Cusa, point out that mental representations and Mind respectively are insufficient for the task. Mind or mental representations have an important role to play in the education of the human being and gaining knowledge about the dead world of matter. However, they must be transcended if we seek knowledge of the Supermind or Spiritual-Self and its relation to the spirit worlds/planes.

It is also important here to address Kant’s position in this question. Kant was essentially motivated to investigate the limits of human knowledge. This was a response to Hume’s empiricism and skepticism about the validity of any knowledge whatsoever because it is rooted in sensory impressions. However, in his attempts to reconcile the conflict between empiricism and rationalism (matter and spirit) and thereby rescue knowledge from the clutches of Humean skepticism he also further ensnared and limited knowledge by denying human beings the possibility of a priori knowledge (knowledge independent of sense experience) in all fields other than in mathematics.

Thus, in Cusa’s notion of intellectual seeing we have an ability that transcends ordinary sense perception and discursive reason for arriving at knowledge. For Cusa the faculty of intellectual seeing is that which is required for insight into deeper spiritual truths. (Later we will address the question of how to develop this faculty according to Steiner and Aurobindo). Kant transcends Hume’s skepticism, but limits non-empirical knowledge (a priori) to the realm of mathematics and logic. The rest of existence is subsumed into the unknowable metaphysical construct of “Das Ding an Sich” (The thing in itself). In a curious way we can also see that Kant affirms certain aspects of Cusa’s assertions on knowledge, whilst denying other aspects because of his own dependence on discursive reasoning. One way to understand this curious development in the storyline of philosophy would to call it a Kantian reversion to scholasticism.

Learned Ignorance

Before moving on, let’s summarize the above so that we can better understand the contributions of Steiner and Aurobindo that will follow below. Human thinking, to the extent that it is bound to empirical evidence, feels a sense of certainty and connection to the reality of the senses. This is so because our conceptual life helps us to make sense of the impressions of the senses. However, the dominance of the senses, empirical evidence, tends to reject any experience that comes from outside that realm. An extreme expression of the this position is: “Seeing is Believing” or “”I’ll believe it when I see it.”. This rejection itself can be based in a fear of losing one’s certainty or even sense of self. Alternatively, this rejection may reflect in a healthy respect for the challenge of the immense task that faces every human being with regards to realizing one’s own learned ignorance and striving towards awakening an intellectual seeing.

Goethe

We need to introduce one further concept to the mix to facilitate the reconciliation of our cosmic Hegelian dialectic. In Goethe’s scientific writing we are confronted with the interesting concept of polarity and intensification (Polarität und Steigerung) which are important tools for reconciling what initially seem to be opposite forces.

Polarity

At the heart of the concept of polarity is that the notion of a harmonious interplay between opposing elements. Consequently, opposites are not in conflict but rather complement and enrich each other. This is at the heart of Goethe’s experiments and exploration of the phenomena of light and darkness, which lead to a fundamentally different appreciation of what colour is compared to Newton’s, unipolar, theory of light. In the field of botany Goethe proposed that all plant organs are variations of the fundamental leaf form, a polarity, which is continuously in living transformation as a result of the Urpflanze (archetypal plant) interacting with the different physical environments. This ability to find unity in diversity, to see beyond the differences to recognize a higher unity is deeply characteristic of Goethe’s approach to science and is thoroughly investigated in Steiner’s works Goethean Science GA 01 (Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften) and The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe’s World Conception GA 02 (Grundlinien einer Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf Schiller”. Also of note is the statement that Goethe made to Schiller with regards to being able to see this archetypal plant, as this is in tone similar to the intellectual seeing that we looked at with regards to Nicholas of Cusa.

Philosophically, Goethe benefited far more from Schiller than from Kant. Through him, namely, Goethe was really brought one stage further in the recognition of his own way of viewing things. Up to the time of that first famous conversation with Schiller, Goethe had practiced a certain way of viewing the world. He had observed plants, found that an archetypal plant underlies them, and derived the individual forms from it. This archetypal plant (and also a corresponding archetypal animal) had taken shape in his spirit, was useful to him in explaining the relevant phenomena. But he had never reflected upon what this archetypal plant was in its essential nature. Schiller opened his eyes by saying to him: It is an idea. Only from then on is Goethe aware of his idealism. Up until that conversation, he calls the archetypal plant an experience for he believed he saw it with his eyes.

GA 1, chapter 11

Nicholas of Cusa was also familiar with this concept of polarity as understood by Goethe. He considered geometry as an excellent means of training the mind for considering how geometrical figures can be deformed and transformed and thus attaining a coincidence of opposites (Coincidentia oppositorum). Readers of Steiner will also be similarly aware of the significance that geometry played in his own development and which recounts in chapter 1 of his autobiography.

Soon after my entrance into the Neudörfl school, I found a book on geometry in his room. I was on such good terms with the teacher that I was permitted at once to borrow the book for my own use. I plunged into it with enthusiasm. For weeks at a time my mind it was filled with coincidences, similarities between triangles, squares, polygons; I racked my brains over the question: Where do parallel lines actually meet? The theorem of Pythagoras fascinated me. That one can live within the mind in the shaping of forms perceived only within oneself, entirely without impression upon the external senses – this gave me the deepest satisfaction. I found in this a solace for the unhappiness which my unanswered questions had caused me. To be able to lay hold upon something in the spirit alone brought to me an inner joy. I am sure that I learned first in geometry to experience this joy.

GA 28, chapter 1

Intensificaton (Steigerung)

Intensification in the context of Goethe means a detailed study of the phenomena of transformation that reveal other deeper hidden patterns. This process of intensification or gradual enhancement in turn leads to higher states of consciousness/existence. By focusing on the way in which polarities transform in a living way then becomes a means of knowing at a deeper level more about the spiritual being or archetype underlying the observed changes. Intensification with Goethe leads to a deeper understanding of the underlying unity of nature. This phenomenological approach is deeply characteristic of Goethe’s scientific method. If we enter into the essence of Goethe’s conceptual pair we might also like to describe as an experiential version of Hegel’s abstract philosophical dialectical model.

Aurobindo

The above was a long introduction to enable us to understand the significance of a specific aspect of what Aurobindo describes in chapter 25, The Triple Transformation in his work The Life Divine. Earlier in the book he has already tackled the reason for and the value of the limited knowledge of Mind in the context of an evolution of consciousness. In this chapter there is a greater focus on the methods or practices that can be undertaken to transcend mere Mind consciousness, which as he states below is the goal of Nature herself.

There is a will in her to effectuate a true manifestation of the embodied life of the Spirit, to complete what she has begun by a passage from the Ignorance to the Knowledge, to throw off her mask and to reveal herself as the luminous Consciousness-Force carrying in her the eternal Existence and its universal Delight of being.

The Triple Transformation

Here he is telling us that Nature has a plan for us, she intends for us to become the crowning achievement of her own creation. However, we are still far from reaching those heights, Nature has far from accomplished her goal. In us she has placed a seed which must be cultivated by the content of our soul lives so that in that soul awareness and then direct experience of our own spiritual and eternal nature will slowly reveal itself. He points to the necessity of the involvement of the will in this process.

But even so this evolution would be slow and long if left solely to the difficult automatic action of the evolutionary Energy; it is only when man awakes to the knowledge of the soul and feels a need to bring it to the front and make it the master of his life and action that a quicker conscious method of evolution intervenes and a psychic transformation becomes possible.

The Triple Transformation

Purusha and Prakriti

At this stage of a journey with Aurobindo we are 955 pages into his complex and profound exploration of the nature of reality and spiritual truths. This also means we are likely interested in learning about methods by which we might move beyond mere Mind to Supermind. Whilst some readers of Aurobindo might be satisfied with the mental challenge of understanding Aurobindo’s philosophical framework, others will inevitably ask the question. How do we intervene in this psychic transformation process? What practices might we consider to accelerate the process? How might we develop the intuitus intellectualis talked about by Nicholas of Cusa. How might we discern Goethe’s archetypal plant, The Urpflanze. He answers us in the following way:

One effective way often used to facilitate this entry into the inner self is the separation of the Purusha, the conscious being, from the Prakriti, the formulated nature.

The Triple Transformation

What can we say about this method? Quite simply, this is the process of polarization and intensification that we discovered at the heart of Goethe’s scientific method. We will also later see that it is at the heart of the Michaelic Yoga that Steiner talks about in several of his later lectures.

Aurobindo reminds us that by standing back from the activities the mind, letting them fall silent at will or alternatively observing them as a detached and disinterested witness we intensify the experience of the insight that we are pure mental beings, Purusha. Also by standing back from life activities, refraining from outer action, we furthermore intensify the direct experience that we are pure vital beings, Purusha. Thus by standing back from these activities it becomes possible to realise one’s inner being as the silent impersonal self, the witness Purusha. In this experience we liberate our spirit from its confines, mental and physical.

The Ashtavakra Gita expresses this same idea somewhat radically in the following manner.

Janaka said: Master, how is Knowledge to be achieved, detachment acquired, liberation attained?

Ashtavakra said: To be free, shun the experiences of the senses like poison. Turn your attention to forgiveness, sincerity, kindness, simplicity, truth. You are not earth, water, fire or air. Nor are you empty space. Liberation is to know yourself as Awareness alone—the Witness of these. Abide in Awareness with no illusion of person. You will be instantly free and at peace.

Ashtavakra Gita

This liberation will, however, not lead to the transformation that Aurobindo is aiming for. Such a Purusha freed from the shackles that held it fast may leave Nature, Prakriti content to be a spiritual being that has no connection with the Earth, its inhabitants. The temptation will be strong to leave all worldly worries behind. Illness and suffering have no place in Purusha. This blissful state also has a dark side, it can lead to the most intense forms of egotism. This intensification of the ego is an inevitable consequence of spiritual development. The important question then becomes: Do I use this strengthened awareness of my god-like nature to bask in my own glory, to seek power in a Nietzschean like combat, to satisfy my own desires or do I use this new found awareness of my own divinity to consciously further the will of Brahman, Krishna or the Cosmic Purusha?

We are faced with the same question that Arjuna faced on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. Krishna had initiated Arjuna into the essence of his true spiritual (Purusha) nature, the significance of karma and reincarnation. That question is: What is the point of living as I wake up to my own eternal unbegottenness and immortality. Why live on Earth and in the confines of Prakriti if I am spirit? Arjuna fought against the blood ties that would destroy him, he aligned himself with Krishna to fight against that which wanted to destroy him. Today, those forces are the death forces of materialism and the modern Arjuna fights for a society that lives in a conscious connection with those cosmic forces that promote Truth, Beauty and Goodness. Those forces that foster a thinking that longs for and engages itself in revealing Truth. Those forces that awaken in the feeling life a joy for what lives in the world. Those forces that will to act so that Good deeds are performed. These death forces must be spiritualized to create a heaven on earth for all. Thus the freed Purusha in us must choose to lovingly invite those forces, spiritual beings, into itself to be part of creating the grand vision of Brahman, Krishna or the Cosmic Purursha.

How do we become conduits for these forces? Aurobindo is also clear in this respect and repeats and clarifies what was expressed in the Bhagavad Gita. It is a concept that is found in all true religions, namely the conscious choice to serve the highest God, Divine Being, Brahman, Ishwara that created mankind in its image and wants nothing more than for that image to realize its true divine heritage. (N.B. the name is of less importance, of greater importance is what we mean when we use the name. What is its conceptual content?)

The method of detachment from the insistence of all mental and vital and physical claims and calls and impulsions, a concentration in the heart, austerity, self-purification and rejection of the old mind movements and life movements, rejection of the ego of desire, rejection of false needs and false habits, are all useful aids to this difficult passage: but the strongest, most central way is to found all such or other methods on a self-offering and surrender of ourselves and of our parts of nature to the Divine Being, the Ishwara.

The Triple Transformation

Thus we see that Aurobindo distances himself clearly from the idea of escaping from Maya, the great illusion of the physical plane. We have seen in other articles how he rejects Eastern streams of thought, especially some interpretations of Buddhism, that deviate from this Vedic understanding. The meaning of our life is consequently to re-connect in a conscious manner with the world from which we descended. If we connect consciously with the source of life we can bring its healing forces into our relationships and societal structures. If we fail to do so and continue to deny the spirit by adhering to materialism we will unconsciously introduce more destruction into the world. In this sense Aurobindo is reinforcing a central truth of Vedic wisdom. The Isha Upanishad expresses it in the following manner.

Behold the universe in the glory of God: and all that lives and moves on earth.

Leaving the transient, find joy in the Eternal : set not your heart on another’s possession.

Working thus, a man may wish for a life of a hundred years.

Only actions done in God bind not the soul of man.

There are demon-haunted worlds, regions of utter darkness. Whoever in life denies the Spirit falls into that darkness of death.

Isha Upanishad

Steiner

Michaelic Thinking

We have seen how Aurobindo describes a path to take us beyond Mind. This leads us to the question: How does Steiner describe the path towards overcoming the limits of knowledge that are real for a certain type of thinking, a type of thinking that is a necessary pre-requisite for that one to be developed?

In GA 194, The Mission of the Archangel Michael, but also other lectures, Steiner goes into substantial detail regarding this question and my purpose here to highlight a couple of key ideas that are developed in this series of 12 lectures in Dornach 1919, 21 November to 15 December.

For Steiner, Michael’s mission consists in the spiritualization of thinking. One way of describing what this means is that humanity has the task of redeeming thinking so that it can learn to see again the underlying spiritual nature of reality, the one that is veiled by the experience of the senses. In the lecture from 14th December 1919 he also makes clear that within the true nature of thinking there is also a will force. Students who have worked with the Philosophy of Freedom will also understand the philosophical underpinnings to this radically un-Kantian understanding of what thinking is.

Let us then look at one line of thinking Steiner uses to develop the spiritualization of thinking. Let us consider the phenomena of magnetism, electricity and light and ask ourselves whether our senses can ever perceive these forces. A brief consideration of this question soon leads us to conclude that we never directly see neither magnetism nor electricity, instead we only ever see the effects on material bodies. The compass moves according to lines of magnetic force, yet we never see that force. Electricity passed through a wire may lead to heating, yet we never perceive the electricity itself. This is also the case with light if we move beyond superficial thinking. Light itself is invisible, it only becomes visible when it interacts with matter.

If we further develop this line of thinking and then consider what the human being is from a spiritual scientific perspective we can also describe in the same fashion, namely it as an invisible being that attracts matter to it. A magnet attracts iron filing according to a certain lawfulness and similarly the human being is an invisible being that becomes evident to the senses for the same reason. The same line of thinking can also be used to show that a plant is an invisible body of forces that structures elements of the mineral kingdom according to a lawfulness that doesn’t belong to the mineral kingdom itself. An identical line of thinking is also valid for considering the animal kingdom as the manifestation of invisible forces. In the lecture GA194, 23 Nov 1919 this is expressed thus:

To say this to oneself with full consciousness at every moment of waking life constitutes the Michaelic mode of thinking; to cease conceiving of the human being as a conglomerate of mineral particles which he but arranges in a certain way, as is also assumed of animals and plants and from which only the minerals are excepted, and to become conscious of the fact that we walk among invisible human beings — this means to think Michaelically.

GA 194

The thought of “walking amongst invisible human beings” that Steiner is forcing us to confront here is that our lives are filled with meetings with beings that would be invisible to us if we lacked the sensory equipment to perceive them. However, if we persist in this thought we also realize that unless we develop new forms of perception (in anthroposophy it is more common to talk in terms of other levels of consciousness) we can only ever have indirect awareness of these invisible beings. We are conscious of the mineral realm through our senses, but consciousness of the invisible realm of plant life requires a new consciousness. This is referred to as either imaginative or pictorial consciousness or etheric vision. To perceive and know the invisible beings of the animal realm requires inspirational consciousness or astral hearing. The invisible being behind the human being is accessible to intuitive consciousness.

These different levels of consciousness give the promise of deeper levels of understanding of those currently invisible realms as the human being evolves new higher forms of consciousness. However, the above fact also obliges us to recognize the possibility that there could well be beings not made present to the senses, not clothed in the cloth of atoms, but which nevertheless have both a real existence and real effects on the inner lives of human beings. Two central forces that are continually at play in the human being and can only be known indirectly, unless the required level of consciousness is developed, are the Luciferic and Ahrimanic forces.

Concentration and meditation

Steiner talks on numerous occasions about how these invisible worlds can, through schooling, become directly perceptible to anybody prepared to dedicate the time and effort required. The most comprehensive books from this perspective are “Knowledge of Higher Worlds”, “Esoteric Science” and “Theosophy”, but it is worth pointing out this question is illuminated from dozens of other perspectives in different lecture series.

Nevertheless, we can still talk about a common denominator which will be immediately recognizable to anybody familiar with oriental thinking. Earlier I quoted the Ashtavakra Gita as essentially pointing to the same path. This involves first silencing the senses. Silencing thinking that concerns the events of the outer world and developing the ability to concentrate on a single and specific thought, image, phrase and to observe how the inner life is pulled this way and that by the life inherent in thinking. The pupil must use his will to prevent himself from being pulled hither and thither and instead focus on the chosen content of for his consciousness. By acting in this manner the pupil is taking control over the inner life by for a given period of time, being the sole determiner of the content of the soul. The pupil through his own inner strength brings the inner winds, gusts and storms that normally carry his soul life to an inner calm. After months, years or decades of practise, depending on the amount of practise and personal karma, these inner winds can be stilled completely. This is the same stillness of mind that allows us to fall asleep, however, in the case of the pupil who has attained a certain inner strength consciousness is not lost. In this state this inner space that has been created becomes an inner space in which pupil can enter into dialogue with a part of himself that transcends his normal consciousness. Whether this previously hidden part of the inner life is called the Self, Purusha, Higher-Self or other is of little importance. What is important is that this hidden aspect that occasionally revealed its activity in the dream life, in ideas and inspirations, in lucid moments of creativity and in understanding something at a new level (levelling up), this aspect becomes more integrated into the pupils own understanding of what he is. Socrates descriptions of his Daimon are a good example of someone who was conscious of a deeper being of wisdom that lived in him, but was at the same time not him.

Philosophy of Freedom

Steiner tells us that all the fruits of the results of spiritual science that he developed in his life work can be found in seed like form in his book from 1894 “The Philosophy of Freedom” (also called Philosophy of Spiritual Activity or Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path). The central argument in the books is that we can never talk about free human action unless we know the causes of our actions. However, before that investigation of the causes can even begin we have to thoroughly investigate the activity of thinking to understand what thinking is able to tell us about the world and ourselves. As we become clearer about the relationship of thinking to the inner and outer world, we are also waking up to a part of our soul that often remains unexamined. This deepening or individualization process can lead to ever deeper strata of understanding and participation in life. Indeed, it will lead to an ever deepening conscious experience of the eternal in man. This book allows us to find a region of soul that can become a well from which the human soul can always draw when it is in need of the water of life.

The fact that this deepening is the result of an increased clarity about an essential aspect of each individual’s being is extremely important. The importance lies in the fact that nothing need be believed on the basis of authority to attain this spiritual growth. A deepening of self-knowledge and the knowledge creating ability that lives within each human being, namely thinking, is the only pre-requisite for a spiritual awakening. This means no guru or master is needed in the process of self-awakening. This does not mean that gurus or masters cannot be useful in the process, it just means that they are not obligatory. The less we accept things on authority and the more they can be grounded in direct experience the greater the freedom acquired for our own being. Drawing another parallel with Socrates the assumption is made that an honest investigation in dialogue with oneself and others can lead to a spiritual awakening.

One of the fruits of reading the Philosophy of Freedom can be a crystal clear experience of how when seeing without thinking we are blind. We truly see with our thoughts! The role of concepts and ideas become far clearer in our own understanding of life and ourselves. Consequently, we also understand the importance of developing new concepts and ideas to make sense of the material, soul and spirit worlds that we inhabit. One of the chief challenges to be overcome on this path is to mistake the products of the activity of thinking for the activity itself. As we approach this activity time and time again, without being sucked into the vortex of specific thoughts, we experience a new dimension growing in ourselves. This is the seed of freedom.

Purification

One final important element that also needs to be mentioned here is that of purification. All religious streams in the world encourage the development of a healthy moral character. One that promotes forgiveness, sincerity, kindness, simplicity and truth. Egoism, selfish desires, mendacity and duplicity are all traits that potentially live in us and they must be brought under the control of the I-being so that they cannot have their poisonous effect on the world and our relationship with others. In the context of spiritual awakening such moral development is of extreme importance. This is so because the correcting aspects of normal life that oblige us to live with the results of our mistakes is lost. As we continue consciously down the path of spiritual development we learn how our own inner realities become the world we live in. We live increasingly as if in a mirror image brought to life. If I cultivate a life of forgiveness, sincerity, kindness, simplicity and truth then we will find that in the world. If on the other hand we let egoism, selfish desires, mendacity and duplicity be the dominant forces in our inner life then we also will find that in the world.

Recent Comments