In the wisdom of the Upanishads and their inherent Advaita Vedanta philosophy we can find expressed in poetic language some of the deepest mysteries concerning knowledge of the self and knowledge of the world. These are the self same mysteries that German idealism grappled with and which will be the central topic of this article.

Who sends the mind to wander afar? Who first drives life

to start on its journey? Who impels us to utter these words?

Who is the Spirit behind the eye and the ear?

…

What cannot be thought with the mind, but that whereby

the mind can think: Know that alone to be Brahman, the

Spirit; and not what people here adore.

What cannot be seen with the eye, but that whereby the

eye can see: Know that alone to be Brahman, the Spirit;

and not what people here adore.

What cannot be heard with the ear, but that whereby the

ear can hear: Know that alone to be Brahman, the Spirit;

and not what people here adore.

What cannot be indrawn with breath, but that whereby

breath is indrawn: Know that alone to be Brahman, the

Spirit; and not what people here adore.

Kena Upanishad

This expansive dissolving juxtaposition of words can awaken in more sensitive souls a feeling for that hidden reality which is present between the words. They can feel the tension of having eyes and ears yet at the same marvelling that Nature could produce such amazingly complex wisdom filled organs of perception. However, that sensitive soul also realizes that something far greater, far more discombobulating is also hidden in plain sight, namely the stupendous mystery that it can see and hear at all. Who is that Being? These are the same mysteries that we find J.G. Fichte , F.W.J Schelling and C.G. Jung attempting to clarify and bring to life for the modern mind.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Fichte, like Descartes, was looking for the foundation and guarantor for knowledge and self-existence. The English empiricists (Bacon, Locke) and French sceptics (Montaigne, Charron) had undermined the very notion of being able to attain true knowledge. Descartes, by recognizing that he doubted, ie taking Scepticism to heart, also recognized that something, namely Descartes himself, thought and therefore he existed. This lead to the now widely recognized idea “Cogito ergo sum”, I think therefore I am. Already here we find evidence of the “beating heart of philosophy”, namely the immersion of the soul in a philosophical view which also leads to reveal the inherent contradictions of that view. This is the polarity of perspective.

At last I have discovered it—thought; this alone is inseparable from me. I am, I exist—that is certain. But for how long? For as long as I am thinking. For it could be that were I totally to cease from thinking, I should totally cease to exist. At present I am not admitting anything except what is necessarily true. I am, then, in the strict sense only a thing that thinks; that is, I am a mind, or intelligence, or intellect, or reason—words whose meaning I have been ignorant of until now. But for all that I am a thing that is real and that truly exists. But what kind of a thing? I have said it already: a thing that thinks.”

Meditations on First Philosophy, René Descartes

Fichte, however, was driven to go even further, taking to heart Descartes own words “For it could be that were I totally to cease from thinking, I should totally cease to exist.” Fichte was looking for something akin to the earlier quoted poets of the Upanishads, namely “that whereby the mind can think”. Trying to imagine our way into Fichte’s soul we might hear him uttering the following doubt. “Descartes finds his certainty of existence in knowing that he thinks, but what if thinking is just an illusion and tells me nothing about objective reality nor the ultimate truth. What if with thinking we are only falling deeper into a subjective abyss. In this abyss lurks the danger of solipsism where thinking becomes self-referential and disconnected from truth. I cannot talk about certainties until I know what thinking itself is.”

“To say that I think, therefore I am, is to remain on the surface of consciousness. The deeper question is: What is this ‘I’ that thinks? What is the act of thinking itself? If we do not understand this, then all certainty is illusory, for we have not grasped the ground of our own being.”

Fichte: Introductions to the Wissenschaftslehre (1797)

Fichte sought his way out of that perceived “subjective abyss” by making thinking the object of thinking itself. In normal everyday life we are the thinking subject and objects become either the subject or object of our thinking depending on our philosophical lens. So are the objects the subject or object of our thinking? Let’s use our thinking to consider how both might be considered valid.

- Many of our everyday thoughts refer to objects given to us by the senses and might therefore be considered objects of our thinking.

- Our thinking is an activity that occurs in the subject doing the thinking, so when we turn away from the data of the senses and engage in philosophical thought we are dealing with content that appears to be created by the subject. What was previously object appears to become subject.

- Let us call the former [sense] objects and the latter [spirit] objects or [subject] objects. Thus [spirit] objects are the internal, conceptual entities created by the subject’s own thinking activity, distinct from [sense] objects. Following Fichte, we can distinguish [sense] objects as the external not-I and [spirit] objects as the internal products of the I’s self-positing. This does not exclude the possibility that [sense] objects are manifestations of [spirit] objects which remain unknown to the I. The latter are commonly called concepts in philosophy.

Thus when we think about our thinking we discover in our own experience the non-static nature of the subject-object dichotomy. This insight is in stark contrast to Descartes strict mind-body or self-world duality and creates a tension. Earlier we reflected briefly on the “the polarity of perspective”, tension of opposites, as being the source of energy for philosophical discovery. Here we find ourselves again in a fluid polarity, namely of the subject-object and Fichte wants to find a region of the soul that can live and thrive in those waters.

This is achieved by recognizing another discovery that can be made by thinking about thinking, namely that prior to thinking, eg as a very young child, consciousness of my self did not exist. I existed for others, but not for myself. My concept of I is itself a fruit of thinking. By the grace of thinking my I comes into existence.

Das Ich setzt ursprünglich schlechthin sich selbst, und es ist, in diesem Setzen, vor aller Teilung des Ich und Nicht-Ich.”

The I originally and absolutely posits itself, and it is, in this positing, prior to any division of the I and the not-I.”

Grundlage der gesammten Wissenschaftslehre

In asserting that the “I” doesn’t exist independently, but that it comes into being through an act of self-positing Fichte is anticipating what will become basic principles of theories of psychological development. The “I” is not a static [spirit] object but a dynamic process or [spirit] activity that creates itself. This self-positing of the I as a creative acts also leads to a new polarity, namely the not-I.

“Das Ich setzt sich als sich selbst bestimmend, und dieses Sich-Bestimmen ist das Wesen des Ich.”

“The I posits itself as self-determining, and this self-determination is the essence of the I.”

…

“Das Ich ist nicht ein Sein, sondern ein Thun; sein Sein besteht darin, dass es sich selbst setzt.”

“The I is not a being, but a doing; its being consists in the fact that it posits itself.”

…

“Ich bin, weil ich mir selbst bewusst bin; und dieses Bewusstsein ist ein Akt, durch welchen ich mich selbst schaffe.”

“I am because I am conscious of myself; and this consciousness is an act through which I create myself.”

As we let Fichte’s words become [spirit] objects for our thinking we also feel the solidity of his experience, its will-like character unencumbered by external factors when he uses the words “self-determining”, “not a being, but a doing” and “through which I create myself”. Yet at the same time we remain aware that it is the activity of the I that implicitly creates the not-I. The division of experience into I and not-I is a result of thinking, but which also points to an absolute-I which was initially infinite and undefined, but limited itself to gain consciousness of self. This is not a conclusion that Fichte comes to directly though he might have considered it due to his familiarity with Jacob Böhme’s thinking and possibly also the concept of the Urgrund (Abyss) an infinite, undefined ground, which itself is akin to ideas found in other traditions, for example the Ein Sof of the Zohar, the Nirguna Brahman of Advaita Vedanta philosophy, as above in the Kena Upanishad, the Para Brahman of the Bhagavad Gita and the initial state described in Genesis in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Nevertheless, as we will see below with Schelling, also deeply familiar with Jacob Böhme, this is a grounded interpretation of where Fichte may have developed his thinking and indeed his son Immanuel Fichte did.

“Die Begrenzung des Ich durch das Nicht-Ich ist die Bedingung seiner Selbstbewusstsein”

“The limitation of the I by the not-I is the condition of its self-consciousness”

A legitimate question arises here. If the I has through it own activity posited itself into existence then we are naturally led to ask out of what substance does this I consciousness produce itself. This action must be performed in a medium. What might this medium be? Returning to the young child that has no concept of I we can see how this precedes the formation of I consciousness. What was this pre-I state? Fichte is unable to provide an answer to this question because he wanted to avoid using metaphysical explanations. It is for this reason that we now turn to Schelling.

Schelling

As we saw in the previous section Fichte’s emphasizes the I’s role in unifying subject and object by integrating the not-I. Schelling perceived the centrality of the so called Absolute-I in Fichte’s epistemology to be problematic as it failed to account for the reality of the object. Schelling succeeds in expanding the notion of the I and frames it as a broader ontological and existential act, not just an epistemological one. Indeed, the depth and scope of what Schelling proposes is so broad that it posits a [spirit) object (idea) that serves as a foundation for all creation. It finds a transcendent point out of which the subject and the object dynamically emerge. The “tension of opposites” yields a new principle which appears capable of bearing the full weight of [sense] objects and [spirit] objects ([subject] objects).

Schelling’s [spirit] object that serves as this p rinciple is the Absolute. As with Böhme’s Urgrund (Abyss, archetypal foundation) Schelling posits a primal unity, a completely undifferentiated state, in which there can be no distinction between subject and object because this is the undifferentiated state (Hegel: sublated) that defines the polarity, but is not that polarity. It is pure and infinite potentiality. This primal identity adopts some form of manifestation, say physical matter. Then this same primal identity out of its infinite being uses that matter to manifest another aspect of itself within the now present physical matter. This matter then serves as a foundation for the a manifestation of its inherent creative activity, an aspect of its identity. As a more concrete example we can use Goethe’s idea of the Urplanze (archetypal plant) to illustrate more clearly. A plant is inconceivable without matter, or at the very least invisible to the senses. However, reducing the plant to mere matter is to completely miss the very real system of complex processes (activity) that must occur in a specific order if a plant is to develop from seed to maturity and then to produce itself again. Dead matter cannot achieve this process, this unfolding process, is the manifestation of other principles implicit in Schelling’s Absolute. Thus Goethe’s Urplanze could be interpreted as a [spirit] object which manifests itself as a [sense] object yet both this and the [sense] object of matter are manifestations of the Primal Identity/Absolute which is the primal [spirit) Object out of which all [spirit] and [sense] objects emerge Schelling gives a rich description this pre-polar state thus:

“Das Absolute ist die ewige, unbewußte Grundlage der Harmonie zwischen dem Subjektiven und Objektivem, und es wird niemals ein Objekt des Bewußtseins, weil es in seiner absoluten Einfachheit keine Dualität zuläßt. Es ist das, was in sich selbst ruht und doch die Quelle aller Bewegung und Entwicklung ist. Das Absolute ist nicht etwas, das wir erfassen können, sondern es ist das, worin wir uns selbst und die Welt begreifen.”

System des transzendentalen Idealismus: Praktische Philosophie

The Absolute is the eternal, unconscious basis of the harmony between the subjective and the objective, and it never becomes an object of consciousness because in its absolute simplicity it does not allow for duality. It is that which rests in itself and yet is the source of all movement and development. The absolute is not something that we can grasp, but it is that in which we understand ourselves and the world

and

“Das Absolute ist die Quelle aller Intelligenzen und vermittelt zwischen dem sich selbst bestimmenden Subjektiven und dem Objektiven oder Intuitiven. Es ist das, was die Einheit von Geist und Natur ermöglicht, indem es die Grundlage für die Wechselwirkung zwischen dem freien Willen und der natürlichen Notwendigkeit bildet. In dieser Vermittlung zeigt sich das Absolute als das, was sowohl das Subjektive als auch das Objektive in sich vereinigt.”

System des transzendentalen Idealismus: Praktische Philosophie

“The Absolute is the source of all intelligences and mediates between the self-determining subjective and the objective or intuitive. It is that which makes the unity of spirit and nature possible by forming the foundation for the interaction between free will and natural necessity. In this mediation, the absolute reveals itself as that which unites both the subjective and the objective in itself.”

Out of this Absolute the pre-cognitional being (das Unvordenkliche) is born and starts its journey towards consciousness, then self-consciousness and finally absolute-consciousness.

Jung

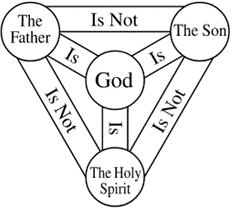

Let us now move to the final part of this essay and consider how Fichte’s self positing I coupled with Schelling’s philosophical ontology might be mapped to the depth of Jung’s psychological insights. We have Schelling’s trinitarian framework of the Absolute (the primal unity), Nature (its material manifestation), and Spirit (its conscious expression) and Jung’s process of individuation which describes the psychological journey of the Self toward wholeness, integrating the conscious ego with the unconscious.

If we consider Jung’s [spirit] object of the Self which represents the totality of the psyche, uniting conscious and unconscious in a pre-differentiated wholeness. The Self is an identity within collective unconscious that contains archetypes shared across humanity. These archetypes, latent potentials, of thinking and behaviour (activity) exist in an undifferentiated form at the birth of the human being, they exist as [spirit] objects, but manifest successively as [subject] objects, forming psychic strata on or in which other archetypes can establish their activity and become a conscious experience for the soul.

Investigation of the psychology of the unconscious confronted me with facts which required the formulation of new concepts. One of these concepts is the self

……

I have suggested calling the total personality which, though present, cannot be fully known, the self. The ego is, by definition, subordinate to the self and is related to it like a part to the whole. Inside the field of consciousness it has, as we say, free will. By this I do not mean anything philosophical, only the well-known psychological fact of “free choice,” or rather the subjective feeling of freedom.

A I O N, Researches into the phenomenology of the Self, Chapter 1

In Fichte the “tension of opposites”, I and not-I led to the so called Absolute-I. Schelling’s “tension of opposites” of Nature and Spirit allowed him to deduce the Absolute. Finally with Jung we see how the dynamic interplay of the unconscious (Schelling’s Nature) and conscious (Schelling’s Spirit) find their origin and unity in Jung [spirit] object, the Self. Schelling’s Nature as a [sense] object becomes in Jung’s psychology a [subject] object, ie an inner experience of consciousness which is real for the individual. Schelling’s Spirit becomes in Jung phenomenological description of the soul the archetype, [spirit] object, ie the impulse that was the source of the inner experience. This differentiation between [subject] object and [spirit] object in turn maps to the distinction between the personal and the universal, awareness of an aspect of the collective unconscious. Psychological development that all human beings subject themselves to starts in a pre-egoical existence. As the human being develops from baby to child to teenager to young adult to middle age to maturity each successive stage of development is rooted in what preceded it. Yet, whilst these stages are crucial for the process of individuation, self-awakening, they do not fully define the trajectory of that path. The impulse for the future trajectory must be provided from beyond consciousness, from a supra-consciousness, which will then become a conscious and known experience for the ego.

My own experience of commentators on Jung is that there appears to be a certain shyness or timidity in talking about possible examples in history for people who have achieved an exceptionally high degree of individuation or arguably even full individuation, full conscious-realization of the Self. For that reason I would like to consider the role of Christ in Jung’s writings using them as means to summarize this essay. Aion is a rich source for this material as Christ appears over 600 times in the book whereas Jesus appears only 60.

These few, familiar references should be sufficient to make the psychological position of the Christ symbol quite clear. Christ exemplifies the archetype of the self. He represents a totality of a divine or heavenly kind, a glorified man, a son of God sine macula peccati, unspotted by sin.

…

“Christ exemplifies the archetype of the Self.”

…

The God-image in man was not destroyed by the Fall but was only damaged and corrupted (“deformed”), and can be restored through God’s grace. The scope of the integration is suggested by the descensus ad inferos, the descent of Christ’s soul to hell, its work of redemption embracing even the dead.

…

For the Church Fathers Christ is this source, means the ground of the soul from which the fourfold river of the Logos bubbles forth.

Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self

In these quotes specifically concerning Christ we can already begin to discern a clear structure which is the same structure that has been the topic of this essay. Christ, the full complete [spirit] Object/Being took up abode in the body of Jesus at an estimated age of 30 at the baptism in the Jordan. Immediately following the baptism Jesus Christ spent 40 days in the desert overcoming the temptations of the Devil and Satan. This is important as it can be read as a refutation of claims that Christ didn’t include the shadow. Quite clearly, according to the Bible, he did and consciously rejected the temptations of those aspects of the Self, but not denying their reality. Christ as the [spirit] Object/Being like all [spirit] object/beings had the objective of manifesting itself so that it could become conscious of itself, no longer remaining in the collective unconscious. However, we also know that Christ was the son of God which could be interpreted as a full revelation of the essence of the theological God of the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Absolute in Schelling’s philosophy or the template of the complete human being, the Self, in Jung’s psychology.

We started this essay with some lines from the Kena Upanishad. Let me leave you with the powerful words that Jung uses to introduce us to what was happening in his soul that led him to write The Red Book (Liber Novus), because they are a part of his answer to the question: “Who is that Being?”.

If I speak in the spirit of this time, I must say: no one and nothing can justify what I must proclaim to you. Justification is superfluous to me, since I have no choice, but I must. I have learned that in addition to the spirit of this time there is still another spirit at work, namely that which rules the depths of everything contemporary: The spirit of this time would like to hear of use and value. I also thought this way, and my humanity still thinks this way. But that other spirit forces me nevertheless to speak, beyond justification, use, and meaning. Filled with human pride and blinded by the presumptuous spirit of the times, I long sought to hold that other spirit away from me. But I did not consider that the spirit of the depths from time immemorial and for all the future possesses a greater power than the spirit of this time, who changes with the generations. The spirit of the depths has subjugated all pride and arrogance to the power of judgment. He took away my belief in science, he robbed me of the joy of explaining and ordering things, and he let devotion to the ideals of this time die out in me. He forced me down to the last and simplest things.

…

But the spirit of the depths spoke to me: “You are an image of the unending world, all the last mysteries of becoming and passing away live in you. If you did not possess all this, how could you know?”

Folio 1: The Way of What is to Come, Liber Novus

Let us imagine that we live in northern climes, ca 58:00 N in the middle of winter. It is 7:30 in the morning, which means the sun will not rise above the horizon for another ca. 1 hour and 20 minutes. We leave the house and walk down the path, there is barely enough light to know whether we are walking on the path or the field next to it. In this weak grey light there are no colours only shades of light and darkness. We continue along the path towards the still darker forest and think about the lack of colour and ask ourselves the question: Is grass green? Our memory tells us that the answer is yes, but experience based uniquely on this dark morning walk would have to answer the same question with no. We continue to walk through the forest and there is more light, though still not enough to perceive anything beyond shades of light and darkness. There is, however, a greater distinction between the light and the dark. As our consciousness contemplates this on going change we might be tempted to believe that the grass is only green when light shines on it. However, if we stay with the phenomenon of light for a while longer we can also call to mind the fact that light itself is invisible. We only know of light’s existence because of matter. This is why we see beams of light if it is shone into a dusty room. If, instead of a room, we shone light through a vacuum chamber we would see nothing in the chamber yet we would see light both entering and exiting such a suitably built chamber.

Let us imagine that we live in northern climes, ca 58:00 N in the middle of winter. It is 7:30 in the morning, which means the sun will not rise above the horizon for another ca. 1 hour and 20 minutes. We leave the house and walk down the path, there is barely enough light to know whether we are walking on the path or the field next to it. In this weak grey light there are no colours only shades of light and darkness. We continue along the path towards the still darker forest and think about the lack of colour and ask ourselves the question: Is grass green? Our memory tells us that the answer is yes, but experience based uniquely on this dark morning walk would have to answer the same question with no. We continue to walk through the forest and there is more light, though still not enough to perceive anything beyond shades of light and darkness. There is, however, a greater distinction between the light and the dark. As our consciousness contemplates this on going change we might be tempted to believe that the grass is only green when light shines on it. However, if we stay with the phenomenon of light for a while longer we can also call to mind the fact that light itself is invisible. We only know of light’s existence because of matter. This is why we see beams of light if it is shone into a dusty room. If, instead of a room, we shone light through a vacuum chamber we would see nothing in the chamber yet we would see light both entering and exiting such a suitably built chamber. Goethe calls colours the deeds of light. This is a particularly rich maxim that captures the active nature of light and how this activity reveals aspects of the world that would otherwise remain unknown . Meanwhile on the walk still more light is available and as we exit the forest and walk up the grassy path to the little cottage we notice that there is a greenness to the path. It is still a grey-green lacking the full vibrancy that we know it will attain later when bathed in sunlight. We can play this out in our own thinking even though the physical senses currently provide contrary information.

Goethe calls colours the deeds of light. This is a particularly rich maxim that captures the active nature of light and how this activity reveals aspects of the world that would otherwise remain unknown . Meanwhile on the walk still more light is available and as we exit the forest and walk up the grassy path to the little cottage we notice that there is a greenness to the path. It is still a grey-green lacking the full vibrancy that we know it will attain later when bathed in sunlight. We can play this out in our own thinking even though the physical senses currently provide contrary information. Out of the Forest

Out of the Forest appearances seem to contradict this statement. Yet at the same time we are in a position to understand that if phenomena are not permeated by the light of thinking then grass is colourless. This is the position of modern scientific theory, where colour loses its quality to become solely an invisible quantity of wavelength and frequency.

appearances seem to contradict this statement. Yet at the same time we are in a position to understand that if phenomena are not permeated by the light of thinking then grass is colourless. This is the position of modern scientific theory, where colour loses its quality to become solely an invisible quantity of wavelength and frequency.

Recent Comments