Intro

Jeff, Kate and I are currently doing a series looking at Rudolf Steiner’s GA 3 Truth and Science on our YT channel, A prologue to the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. Playlist link I have read this book several times, but something “popped” this time, as Jeff likes to say. In chapter 4 The Starting Point of Epistemology whilst Steiner is describing the importance of the “given”, or as he later calls it in the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity “the relationless aggregate”, it became clear to me how he was conceptually describing the relationship of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit to the Godhead, ie the Trinity. Furthermore, because I had also recently read chapter 16, The Triple Status of Supermind, in Aurobindo’s The Life Divine and also ther perceived something conceptually identical to the trinity, I felt that I had to work through the texts again to see if this intuition, this gift from beyond space and time, could withstand further scrutiny. Was it a justified proposition?

If I do a good job in writing this then the reader may be led closer to an experience of an essential part of him or herself and at the same experience a re-connection to some fundamental insights into what is common to all human beings.

Aurobindo

Let us start with Aurobindo’s starting point for his further elucidations on the Divine Supermind, one of the various names he uses and which can be equated with the Godhead.

We have started with the assertion of all existence as one Being whose essential nature is Consciousness, one Consciousness whose active nature is Force or Will; and this Being is Delight, this Consciousness is Delight, this Force or Will is Delight. Eternal and inalienable Bliss of Existence, Bliss of Consciousness, Bliss of Force or Will whether concentrated in itself and at rest or active and creative, this is God and this is ourselves in our essential, our non-phenomenal being.

With Aurobindo’s description of the essential nature Divine Supermind we are simultaneously being introduced to what we are in essence. However, we do not experience ourselves as Supermind, because our own limited Minds deceive us about our own true natures. Vedic wisdom asserts that to realize our own Divine Consciousness and how it plays and delights eternally in this play, we must recognize how our true self is concealed from us by a false self, mental ego or Mind. Therefore, to aspire to awareness of our true divine nature means to unveil the veiled self in us, by transcending Mind and entering into unity with the Supermind. Knowing oneself means at the same time forfeiting through conscious mentality that which is superconscient in us, eternally present, eternally willing and playing and eternally delighting in its own existence. When the divine in us works or plays it rejoices blissfully in what has been created as it lives in our consciousness. Such existence is named Sachchidananda, however even in the Mind we can experience in a diluted form the contentedness of beholding something we have created.

Contentedness can be viewed as a dull reflection in an unpolished mirror of Sachchidananda. Swami Vivekananda, Aurobindo’s guru has described it thus:

“The moment I have realized God sitting in the temple of every human body, the moment I stand in reverence before every human being and see God in him – that moment I am free from bondage, everything that binds vanishes, and I am free.”

Sri Aurobindo himself says

“God is not found in the ego, nor in the intellect, nor in the senses. He is found only in the depths of one’s own being.”

Western readers might be more familiar with mystics like Meister Eckhart, Teresa of Avila, John of the Cross, Julian of Norwich, Jakob Boehme, Hildegard of Bingen, Johannes Tauler, Angelus Silesius or Thomas Traherne or many of the other mystics that shook Europe in the late middle ages.

Meister Eckhart: “The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me; my eye and God’s eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, one love.”

Teresa of Ávila “Let nothing disturb you, let nothing frighten you, all things are passing away: God never changes. Patience obtains all things. Whoever has God lacks nothing; God alone suffices.”

St. John of the Cross: “In the inner stillness where meditation leads, the Spirit secretly anoints the soul and heals our deepest wounds.”

Hildegard of Bingen: “The soul is kissed by God in its innermost regions. With interior yearning, grace and blessing are bestowed. It is a yearning to take on God’s gentle yoke, It is a yearning to give one’s self to God’s Way.”

Angelus Silesius: “God is a pure no-thingness, concealed in His no-thingness. Therefore, whoever possesses Him as something, possesses not Him but what is not He.”

The question that Aurobindo tackles in this chapter is, “Why do we experience limited Mind as opposed to Supermind”, if Supermind is indeed our true nature. Here like Darwinists we must look for a missing link, something in our direct experience that can act as a seed which then needs to be nurtured to lead us towards a full experience of the Supermind or as he also calls it Truth Consciousness. This can in turn lead to the experience of Sachchidananda.

Sachchidananda is spaceless and timeless, it is not nothing, instead it is no-thingness. However, as mortals we live in space and time which was born, in Aurobindo’s presentation of Advaita Vedanta, out of this no-thingness. I will mention in passing that modern science with its description of quantum fields are in certain aspects conceptually identical to the timeless spaceless descriptions of Vedantic thinking. Hence it is fully understandable that many spiritual worldviews feel drawn to using the latest science of quantum theory as a means of illustrating how the world is spiritual in nature. The fact that this is so is also profoundly unsettling for more materialistically inclined minds and Bernado Kastrup witnesses to here:

Where then is the missing link? It is in the trees of the forest we are looking at. If our world of space and time is, as Advaita Vedanta states, a manifestation of no-thingness, then all sense impressions, all experiences themselves whether internal or apparently external are evidence of Sachchidananda when we re-learn to interpret experience through the insight or axiom. This axiom tells us:

The true name of this Causality is Divine Law and the essence of that Law is an inevitable self-development of the truth of the thing that is, as Idea, in the very essence of what is developed; it is a previously fixed determination of relative movements out of the stuff of infinite possibility. That which thus develops all things must be a Knowledge-Will or Conscious-Force; for all manifestation of universe is a play of the Conscious-Force which is the essential nature of existence. But the developing Knowledge-Will cannot be mental; for mind does not know, possess or govern this Law, but is governed by it, is one of its results, moves in the phenomena of the self-development and not at its root, observes as divided things the results of the development and strives in vain to arrive at their source and reality.

Consistent with this axiom, it follows that Mind (mental ego) is also a manifestation, it is not a no-thing, but instead a some-thing whose being is only appearance, manifestation or immanence of that which is infinite in possibility, that which by definition is indescribable, because in describing it we limit it. Instead we must turn to apophatic statements, that is to say we can only make statement about what this non-being is not, like God is not limited by time or space, is formless without attributes, is beyond all concepts and words, is ineffable and beyond all language.

Furthermore, in accordance with this axiom we have to conclude that Mind has its origin in the Knowledge and Will that is one, infinite, all-embracing, all-possessing, all-forming, holding eternally in itself that which it casts into movement and form. The Supermind moves out of non-being into determinative self-knowledge where it perceives truths about itself and also wills into action events in the realm of time and space. The infinite, loses its infiniteness and becomes limited so that it can experience an aspect of itself.

If we consider the modern theory of the Big Bang or Big Bounce for a moment and strip it of its strictly materialistic interpretations, what do we find. We find that according to that theory the whole of existence, all matter, time and space, all life all human experience was born out of a timeless non-spatial emptiness and also that the seed was an infinitely small dimensionless point of infinite density. So also here in the modern theory of the origin of everything we find posited the same concepts that the sages living in ancient India 3,500+ years ago also used to explain to the origin of everything. For believers in scientism this is problematic, but not for lovers of truth.

In this movement from the ultimate reality of the Supermind into time and space, conventional reality, we can see a Purusha-Prakriti or Father-Son dynamic developing. Timeless Being incarnates in space-time and experiences itself as separate limited being. That separate limited being is always a reflection of an aspect of the infinite Being. What is here stated for the Supermind is also true for Cosmic Purusha and Cosmic Prakriti. What is true for each human being is true for the cosmos.

My self is that which supports all beings and constitutes their existence. . . . I am the self which abides within all beings[1]

Within the Supermind we find that there is an inalienable unity of all things, yet at the same time this unity encompasses the manifestation of the One in the Many and the Many in the One. This microcosm / macrocosm description of reality also encompass a third aspect which has remained invisible yet always present in the preceding descriptions, the idea of an evolution in this relationship. Aurobindo describes these three “poises” in the following way

The poises

…. first and primary poise of the Supermind which founds the inalienable unity of things. It is not the pure unitarian consciousness; for that is a timeless and spaceless concentration of Sachchidananda in itself, in which Conscious Force does not cast itself out into any kind of extension and, if it contains the universe at all, contains it in eternal potentiality and not in temporal actuality. This, on the contrary, is an equal self-extension of Sachchidananda all-comprehending, all-possessing, all-constituting.

In the second poise of the Supermind the Divine Consciousness stands back in the idea from the movement which it contains, realising it by a sort of apprehending consciousness, following it, occupying and inhabiting its works, seeming to distribute itself in its forms. In each name and form it would realise itself as the stable Conscious-Self, the same in all; but also it would realise itself as a concentration of Conscious-Self following and supporting the individual play of movement and upholding its differentiation from other play of movement, — the same everywhere in soul-essence, but varying in soul form. This concentration supporting the soul-form would be the individual Divine or Jivatman as distinguished from the universal Divine or one all-constituting self.

A third poise of the Supermind would be attained if the supporting concentration were no longer to stand at the back, as it were, of the movement, inhabiting it with a certain superiority to it and so following and enjoying, but were to project itself into the movement and to be in a way involved in it. Here, the character of the play would be altered, but only in so far as the individual Divine would so predominantly make the play of relations with the universal and with its other forms the practical field of its conscious experience that the realisation of utter unity with them would be only a supreme accompaniment and constant culmination of all experience; but in the higher poise unity would be the dominant and fundamental experience and variation would be only a play of the unity. This tertiary poise would be therefore that of a sort of fundamental blissful dualism in unity — no longer unity qualified by a subordinate dualism — between the individual Divine and its universal source, with all the consequences that would accrue from the maintenance and operation of such a dualism.

In this third poise we have this beautifully mysterious phrase “blissful dualism in unity”. We will later see how this concept is reconcilable with the descriptions of aspects of the ineffable Holy Spirit, but before we do that we shall also investigate a remarkable chapter in Truth and Science which, whilst using completely different language, also points to this same trinity as the fundamental nature of reality. Furthermore it clarifies certain elements of experience that Aurobindo is, so far in my reading, less explicit about and which are of particular relevance for evolving from the Mind to the Supermind.

Steiner

(The knowledge process is a process of development towards freedom)

Poise 1

In the preparatory chapters up to chapter 4 in Truth and Science, A prologue to the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity we learn that Kant’s attempt to establish a true theory of knowledge, epistemology, is fundamentally flawed, because despite his noble attempts to create a non-dogmatic epistemology he and other after him insert dogmatic statements about knowledge into the theory. This has led to the prevalent notion that my thinking is a purely subjective activity and that thinking is an appendage to our experience meaning that we can never really know the true nature of the world, because the “thing in itself” is always unknowable.

First a few words about chapter 4, The Starting Point of Epistemology”, before we get into the important details. Steiner himself expressed on multiple occasions the “seed” like nature of the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and Truth and Science in relation to the whole of Anthroposophy and Spiritual Science. [2] This is an important point to note as Steiner does not take as a point of departure ancient texts of inestimable value, instead he starts with the fundamental question of what is knowledge? This means there is no appeal to any authority other than the reader’s own ability to observe the activity itself. Whilst a similar rigorous observation of the thinking life is present in Aurobindo’s work, this is always presented in the context of Advaita Vedantic axioms.

So what is the correct place according to Steiner to start with a theory of knowledge? It has to be in a realm in which thinking, the producer of knowledge, has not added any predicates. This means we must artificially create a realm of experience of what it would be like to live in a world completely untouched by thinking. Obviously, this realm of experience would be real yet indescribable for the pure and simple reason that we have to think about our experience before we can say anything about it. As Steiner points out:

Before our conceptual activity begins, the world-picture contains neither substance, quality nor cause and effect; distinctions between matter and spirit, body and soul, do not yet exist. Furthermore, any other predicate must also be excluded from the world-picture at this stage. The picture can be considered neither as reality nor as appearance, neither subjective nor objective, neither as chance nor as necessity; whether it is “thing-in-itself,” or mere representation, cannot be decided at this stage. For, as we have seen, knowledge of physics and physiology which leads to a classification of the “given” under one or the other of the above headings, cannot be a basis for a theory of knowledge.

We can compare this unconditional starting point for epistemology with other thinkers from the Western sphere. For example Plotinus argues that the One is absolutely transcendent and beyond all conditions, limitations and distinctions. It is neither subject to change nor multiplicity, but is timeless and unchanging. According to Plotinus contemplation of the nature of this unconditional was a path for gaining conscious experience of the One. Due to Plotinus’ ideas regarding this path of re-ascent his ideas also became very influential in both Christian and Islamic mysticism. However, there is a key difference between Plotinus and Steiner, because the former is describing the One, giving it predicates or attributes in the same way that Advaita Vedanta through Aurobindo describes Sachchidananda. However, Steiner makes a statement that is intuitively and rationally obvious, namely that prior to knowledge we cannot say anything about anything. We can experience something as existing, yet we cannot know anything about that experience until we proceed to think about it. This pre-knowledge state is called the “given” and in the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity also is named the “relationless aggregate”. The “given” is thus totally undefined, it is no-thing yet is the source of everything we can know and experience. At this point it feels justified to equate Steiner’s “given” with Aurobindo’s Sachchidananda from the point of view of what can be said about them. The One, the Given and Sachchidananda are no-thing yet also the source of everything.

Poise 2

Can we also find in Steiner’s epistemology something that coincides conceptually with Aurobindo’s second poise? The answer is yes and I will describe to what extent they coincide.

Within the field of the Given we also have an activity which also has the capacity of taking us beyond the Given and this activity is thinking itself. Thinking also initially appears to us as a given, however it is a given that is intimately bound up with the experience that was involved in the creation of those thoughts. Expressed in another way and even more accurately; the thoughts created themselves in me because of something that I will later identify as my own activity. Naturally these are all descriptions that become possible through the activity of thinking itself. This coincidence of thinking also initially appearing as a Given is deeply significant. The significance lies in the fact that within the unknown Given we also have the activity of thinking which can begin to make the Given knowable. By arriving at this starting point we have in no way made any dogmatic statements about what can be known about the Given. Consequently the dogmatic principles that plagued Kant and other creators of a theory of knowledge talked about in chapter 3 of Truth and Science have been overcome. Starting from within this grand unity about which nothing is known we also discover the activity of thinking that will awaken us step by step to realization that not everything is given in the given. This world of experience that I partake in is initially devoid of any concepts or ideas that allow me to know the world, understand the world. To understand this world I must create concepts and ideas which form the world experience, but which remained hidden to me for as long as I was unconscious of them.

Let us pause here and reflect on what has been said with an example from literature. Jorge Luis Borges is arguably one of the most interesting writers in Spanish of the 20th century. In many of his short stories the book often appears to have prominent or even leading role in the story. What Borges accomplishes in for example “El libro de la arena” is a devotional story to one of humanities most curious inventions, namely the book or books in general. Give a book to any animals and it would be incapable of conceiving, let alone experiencing that a book full of white pages and black ink characters could awaken in the reader a labyrinth of infinite possibilities in the invisible labyrinth of time, “El Jardin de los senderos que se bifurcan”. In the book as a concept, not as an artefact, we have something which approaches the infinite riches as well depravations of life.

Indeed, even the North American Indians whose culture was steeped in veneration for the ‘Great Spirit” could not understand what a book was. As they gradually got to know the Europeans they were fascinated by printed paper on which there were little signs which they took to be small devils.[3]No analysis of the composition of the paper nor the ink will ever reveal what is hidden behind the appearances. Books are accumulations of symbols which we dive into and try and make sense of. Books are emanations of humanity’s ability to think. Each and every one is a manifestation of this ability, it was born out of this ability yet this ability remains eternally unchanging despite all its offspring. What is true for the book is also true for anything to which we can give a name in the whole the human experience. Anything I identify as existent I do so by the grace of thinking and as Steiner states in the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, when I become aware of the full scope of the activity of thinking, I realize that I myself also only exist by the grace of thinking. Without thinking I would remain unknown in the Given. As a thinker that understands how thinking divides up the world into concepts and ideas I become conscious of how the manifestations occurring in time and space all originate from the Given. Aurobindo when describing the second poise described is as “a sort of apprehending consciousness, following it, occupying and inhabiting its works, seeming to distribute itself in its forms”. In the third part of this essay I will make more specific the “Son” aspect of this relationship between the Given and the known, although it may already be transparent to readers already well versed in immersing themselves into the Exceptional State that Steiner mentions in chapter 3 of the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity.

As a final reflection here, we shall also consider another way in which Steiner distinguishes himself from Aurobindo and Advaita Vedanta. Aurobindo posits consciousness as primary and part of Sachchidananda. This is not the case with Steiner.

This directly given world-content includes everything that enters our experience in the widest sense: sensations. perceptions, opinions, feelings, deeds, pictures of dreams and imaginations, representations, concepts and ideas. Illusions and hallucinations too, at this stage are equal to the rest of the world-content. For their relation to other perceptions can be revealed only through observation based on cognition.

When epistemology starts from the assumption that all the elements just mentioned constitute the content of our consciousness, the following question immediately arises: How is it possible for us to go beyond our consciousness and recognize actual existence; where can the leap be made from our subjective experiences to what lies beyond them? When such an assumption is not made, the situation is different. Both consciousness and the representation of the “I” are, to begin with, only parts of the directly given and the relationship of the latter to the two former must be discovered by means of cognition. Cognition is not to be defined in terms of consciousness, but vice versa: both consciousness and the relation between subject and object in terms of cognition. Since the “given” is left without predicate, to begin with, the question arises as to how it is defined at all; how can any start be made with cognition?

This identification of cognition as that by which consciousness knows itself is the clearest departure by Steiner from a purely Advaita Vedanta axiomatic space. Steiner is telling us that whilst consciousness may be essential to cognition, knowing and knowledge it must also be recognized that it is the activity of thinking, the ability to name, cognize and recognize that enables the thinker to recognize thinking as being primary to knowing and not consciousness. Similarly, the relationship between the Given and the Knower cannot happen outside of consciousness, but it is thinking that establishes this relationship.

Poise 3

The third and final poise will now be examined in the light of chapter 4 of Truth and Science. It’s essential nature has already been hinted at above, but it is important present it in a clear relief so that it doesn’t escape our awareness.

We must find the bridge from the world-picture as given, to that other world-picture which we build up by means of cognition. Here, however, we meet with the following difficulty: As long as we merely stare passively at the given we shall never find a point of attack where we can gain a foothold, and from where we can then proceed with cognition. Somewhere in the given we must find a place where we can set to work, where something exists which is akin to cognition. If everything were really only given, we could do no more than merely stare into the external world and stare indifferently into the inner world of our individuality. We would at most be able to describe things as something external to us; we should never be able to understand them. Our concepts would have a purely external relation to that to which they referred; they would not be inwardly related to it. For real cognition depends on finding a sphere somewhere in the given where our cognizing activity does not merely presuppose something given, but finds itself active in the very essence of the given

Expressed in another way, by identifying this distinction between the one and the many, the microcosm and the macrocosm, the immanent and the transcendent, the father and the son we have been making using of the activity of thinking to reconcile the apparent dualism. Indeed if we have thoroughly engaged with chapter 4 we can also begin to experience more intensely the “blissful dualism in unity — no longer unity qualified by a subordinate dualism — between the individual Divine and its universal source” that Aurobindo refers to. In another essay I wrote “Mankind as Bridge” this topic is explored more thoroughly.

In our experience of the world everything is initially, prior to thinking, experienced as the Given. There is only one exception to this, namely in our thinking because in order to experience our thinking we must first produce it. When we recognize ourselves as the creator of concepts and ideas which we than recognize we are performing an action that Kant rejected as impossible. Kant maintained that intellectual seeing, seeing the thought-form itself, was impossible because thinking only refers to objects and does not produce anything itself. However, this is the very nature of a concept, because a concept unites disconnected elements of perception into a unity. This uniting is not a subjective act in the sense that it has no truth value, this is because it is not the thinker that determines the nature of the union of the disconnected elements, instead it is the universal activity of thinking that reveals the conceptual union previously unseen in the Given. Thus, in thinking we have two fundamental actions at work. We have the naming, dividing intellect that identifies all the various manifestations in the Given. Yet thinking also, by means of intuition or reason, is able to awaken us to relationships and connections between the named and divided manifestations, recreating the unity from which the all proceeded and it is the thinking human being that is at the centre of this process of waking up to ever higher understanding concerning the nature of reality. Waking up in truth we liberate ourselves from the bondage of ideas.

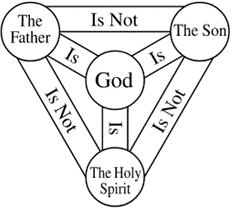

Trinity

The idea of the Trinity of the Godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit is foundational to the Christian faith and is often represented with the following picture:

According to the Bible we are either images of God

Genesis 1:27: “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

2 Corinthians 3:18: “And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit.”

Or indeed Gods themselves

John 10:34 “Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?

Often on Christian websites we find the statements like: “The most difficult thing about the Christian concept of the Trinity is that there is no way to perfectly and completely understand it. The Trinity is a concept that is impossible for any human being to fully understand, let alone explain. God is infinitely greater than we are; therefore, we should not expect to be able to fully understand Him.”

Such answer, whilst being factually true, is uninteresting to a seeker of the truth. What a person full of Truth-Consciousness, or in anthroposophical terms the “Consciousness Soul”, is interested in is: What can I do to better approach, understand and experience the nature of the trinity? I contest that Aurobindo and Steiner in their own ways help us to recognize the way in which God lives in all of us. Aurobindo uses the impeccable logic of Advaita Vedanta to helps us approach and contemplate this highest truth in his exegesis of the three poises. Steiner, on the other hand, invites us to more thoroughly understand the essential nature of the activity of thinking to become more conscious of how the Godhead is present in all experience. We are born of God into the flesh and the Holy Spirit illumines our relationship to our creator. First we believe and then slowly begin to understand how we are Christ-like in our essential nature, i.e. sons of God. As this understanding grows we allow the will of the Father to work through us and we do this in light filled conscious because the Holy Spirit, the helper, is there to guide us.

John 1:12-14 12

But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name: Which were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God. And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father,) full of grace and truth.Angelus Silesius:

Christ became man that we might become God.

In order to find God, one must first lose oneself in Christ.

The Holy Spirit is the breath of God that animates the soul and leads it towards divine union.

Let us look at some other examples of descriptions of the trinity. Saint Augustine of Hippo used the analogy of the Lover, the Beloved and the Love itself to illustrate his conception of the Trinity. The Father is the unbegotten begetter of the and also the Lover of the Son. The Son is the beloved who was begotten by the Father. In Augustine the Holy Spirit is the bond of love between the two. In this description we can recognize the similarity to the concepts developed by both Steiner and Aurobindo. The Father is that out of which everything was created, the no-thing. The Son is that which is immanent and has moved out of the Godhead to take on a specific aspect of the eternal, immutable and infinite creator of all. The Holy Spirit is the knowing of the relationship between the Father and the Son. Both Aurobindo and Steiner have different ways of expressing this same truth, but it is present in both. Aurobindo talked about the “fundamental blissful dualism in unity” as a means of recognizing the awareness of the dual aspects that the unity can exist in. Steiner is equally as clear when he draws attention to the essential role that the spiritual activity of thinking fulfils to unite the Given with the conceptual realms.

Tertullian when describing the Trinity is very similar in style to Aurobindo when he talk about the unity behind the different manifestations of the same essential substance. His analogies like the sun, its light and its heat build on a preexisting understanding unity in diversity. Another analogy he used was that of water which can exist in three distinct form of ice, water and water vapour.

Students of Anthroposophy will not be surprised to learn that Thomas Aquinas had a conception closest in essence to what we find in Rudolf Steiner. Aquinas used analogy of the mind, its knowledge of itself and the love between them to illustrate the fundamental unity of the Trinity. This is not the same as the connection described given above, but I will show how they, in my mind, appear linked.

Aquinas compares the knower to the Father in the Trinity. The Father is the source or origin within the Godhead, the knower is the source of knowledge within the human mind. The knower represents the active aspect of the mind, the subject who engages in the act of knowing. In Steiner this is the I that creates the concepts and ideas in himself which will be recognized in experience, in the Given

Aquinas compares the known to the Son in the Trinity. As the Son proceeds from the Father in the Trinity, the known represents the content or object of knowledge within the human mind. The known refers to the ideas, concepts, or objects that the mind apprehends and understands. In Steiner this is everything that exists in the Given, that which without thinking cannot be recognized as proceeding from the Father. It is beheld in the senses.

Aquinas compares the act of knowing to the Holy Spirit in the Trinity. The act of knowing represents the process by which the mind grasps or comprehends the known. It refers to the movement of knowledge from the knower to the known within the mind. In Steiner, knowledge based in a true epistemology knows that it is the activity of thinking that allows the human being to know of the unitary existence of all phenomena.

[1] Gita IX, 5; X, 20

[2] That is how the whole of the anthroposophical science which has been evolved relates to the seed that was given in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. It must of course be understood that anthroposophy is something alive. It had to be a seed before it could develop further into leaves and all that follows. This fact of being alive is what distinguishes anthroposophical science from the deadness many are aware of today in a ‘wisdom’ that still wants to reject anthroposophy, partly because it cannot, and partly because it will not, understand it.

GA 78 Fruits of Anthroposophy, 3 September 1921, Stuttgart

[3] GA 354, Lecture 8, Dornach, 6th August, 1924

Recent Comments